RESEARCH/REVIEW ARTICLE

Demographic population structure and fungal associations of plants colonizing High Arctic glacier forelands, Petuniabukta, Svalbard

Jakub Těšitel,1 Tamara Těšitelová,1 Alexandra Bernardová,1 Edita Janková Drdová,2 Magdalena Lučanová3,4

& Jitka Klimešová1,5

1 Faculty of Science, University of South Bohemia, Branišovská 31, CZ-370 05 České Budějovice, Czech Republic

2 Institute of Experimental Botany, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, CZ-165 02 Praha 6, Czech Republic

3 Faculty of Science, Charles University, Benátská 2, CZ-128 01 Praha 2, Czech Republic

4 Institute of Botany, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Zámek 1, CZ-252 43 Průhonice, Czech Republic

5 Department of Functional Ecology, Institute of Botany, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Dukelská 145, CZ-379 82 Třeboň, Czech Republic

Abstract

The development of vegetation in Arctic glacier forelands has been described as unidirectional, non-replacement succession characterized by the gradual establishment of species typical for mature tundra with no species turnover. Our study focused on two early colonizers of High Arctic glacier forelands: Saxifraga oppositifolia (Saxifragaceae) and Braya purpurascens (Brassicaceae). While the first species is a common generalist also found in mature old growth tundra communities, the second specializes on disturbed substrate. The demographic population structures of the two study species were investigated along four glacier forelands in Petuniabukta, north Billefjorden, in central Spitsbergen, Svalbard. Young plants of both species occurred exclusively on young substrate, implying that soil conditions are favourable for establishment only before soil crusts develop. We show that while S. oppositifolia persists from pioneer successional stages and is characterized by increased size and flowering, B. purpurascens specializes on disturbed young substrate and does not follow the typical unidirectional, non-replacement succession pattern. Plants at two of the forelands were examined for the presence of root-associated fungi. Fungal genus Olpidium (Fungus incertae sedis) was found along a whole successional gradient in one of the forelands.

Keywords

Colonizer; deglaciation; endophyte; High Arctic; Olpidium; succession.

Correspondence

Jitka Klimešová, Department of Functional Ecology, Institute of Botany, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Dukelská 145, CZ-379 82 Třeboň, Czech Republic.

E-mail: klimesova@butbn.cas.cz

(Published: 30 April 2014)

Polar Research 2014. © 2014 Jakub Těšitel et al. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 Unported License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/), permitting all non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Citation: Polar Research 2014, 33, 20797, http://dx.doi.org/10.3402/polar.v33.20797

Large areas of Arctic and alpine regions have been deglaciated and thus have become open to plant colonization since the end of the Little Ice Age (LIA) about 120 years ago. The boundaries of the last maximum development of glaciers are usually easily distinguished in the field (Rachlewicz et al. 2007), making glacier forelands an outdoor laboratory for the study of plant strategies in cold regions. Colonization of glacier forelands is hindered by a cold and short growing season, small and variable seed production, rough substratum, scarcity of nutrients and organic matter and disturbance by runoff, solifluction, cryoturbation and permafrost (Svoboda & Henry 1987; Chambers 1995; Hodkinson et al. 2003; Moreau et al. 2005; Moreau et al. 2008; Yoshitake et al. 2010).

Plants that are especially successful in primary succession of deglaciated areas are recruited from a pool of stress-tolerant species of cold regions (Caccianiga et al. 2006). These colonizers are dispersed to the deglaciated areas, where seeds germinate at low temperatures and become established (Marcante et al. 2009; Schweinbacher et al. 2012). In contrast to succession on new substrates in temperate regions (e.g., Řehounková & Prach 2010), the early stages of succession in deglaciated areas of the Arctic lack ruderal species characterized by a short lifespan and large investment into fecundity (Moreau et al. 2008; Moreau et al. 2009; Prach & Rachlewicz 2012). That is, in the temperate alpine regions, pioneer plants rapidly colonize recently deglaciated areas within a few years and are replaced with late-successional plant assemblages in the following few decades of succession (Whittaker 1993; Raffl et al. 2006). In the Arctic, in contrast, pioneer plants take decades to colonize and the colonizers often persist in old tundra communities (Svoboda & Henry 1987; Hodkinson et al. 2003; Moreau et al. 2008; Mori et al. 2008; Prach & Rachlewicz 2012). Owing to a reduced species pool and environmental conditions, early successional specialist species are sparse in the High Arctic (Svoboda & Henry 1987) and/or they persist in old growth tundra on disturbed microsites, so their successional status is blurred.

Positive biotic interactions—for example, mycorrhizal symbioses (Nakatsubo et al. 2010; Fujiyoshi et al. 2011), amelioration of substrate by cyanobacterial crusts (Yoshitake et al. 2010) and accumulated organic matter (Hodkinson et al. 2003)—play an important role in early stages of the succession in this low energy environment. It has been suggested that facilitation and competition are rare due to low plant cover (Nakatsubo et al. 2010). During succession in Arctic deglaciated areas substrates change over time. Initially they can be relatively nutrient rich, then reach a quasi-steady-state of development during the fourth or fifth decade due to low precipitation, which limits the mineral weathering (Kabala & Zapart 2012). Only after 60 years do soils develop (Hodkinson et al. 2003). In conjunction with this substrate succession, several studies have reported changing diversity and frequency of root-associated fungi (e.g., Jumpponen 2003; Cazarés et al. 2005; Fujiyoshi et al. 2011). While arbuscular mycorrhiza is generally considered rare at higher latitudes (Newsham et al. 2009), being only rarely reported from Svalbard (Väre et al. 1992; Öpik et al. 2013), it has been suggested that diverse functional groups of fungi (e.g., dark septate endophytes) could influence nutrient uptake and growth in Arctic plants (Newsham et al. 2009). Ectomycorrhiza and association with dark septate endophytes have repeatedly been observed in the Arctic regions (Kohn & Stasovski 1990; Väre et al. 1992; Fujimura & Egger 2012).

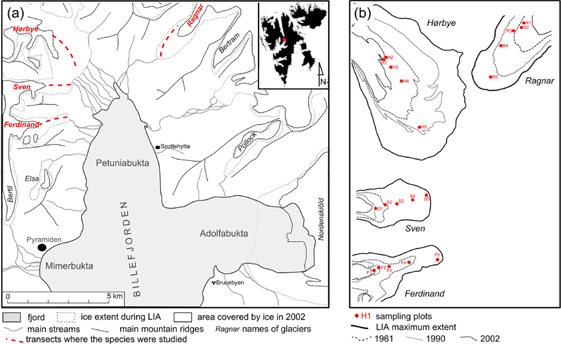

Most pioneer species in the High Arctic are regarded as generalists capable of colonizing young substrate, in addition to other habitats, resulting in the unidirectional, non-replacement succession pattern (Svoboda & Henry 1987; Prach & Rachlewicz 2012). Here, we argue that in addition to these generalists, some pioneer species are specialists restricted to young substrate. The generalist species can be expected to display an increase of size and proportion of flowering individuals (i.e., an ageing pattern) along the successional gradient of time since deglaciation. By contrast, an early-succession specialist should depend more on local conditions and population structure should be more or less independent of the time elapsed since deglaciation. To identify these patterns, we investigated demographic population structures of two pioneer species—a widely spread generalist, Saxifraga oppositifolia, and an assumed specialist, Braya purpurascens—along the successional gradients of four glacier forelands in the Petuniabukta area, northern Billefjorden, Spitsbergen (Fig. 1). Further, to contribute to our understanding of the role of fungal symbioses in succession in the High Arctic, we examined roots of the two species for the presence of root-associated fungi on two of the forelands.

Fig. 1

(a) Map of studied area of Petuniabukta. The studied glacier forelands are marked with dashed lines. The inset shows the location of northern Billefjorden on the island of Spitsbergen. (b) The glacier forelands involved in the study with reconstructed positions of glacier foreheads since the Little Ice Age (LIA) maximum (based on Rachlewicz et al. 2007). The red circles depict positions of the study sites.

Materials and methods

Study species

Saxifraga oppositifolia (Saxifragaceae) and Braya purpurascens (Brassicaceae) have been reported as pioneer species in glacier foreland succession in Svalbard (Hodkinson et al. 2003; Moreau et al. 2008; Nakatsubo et al. 2010; Prach & Rachlewicz 2012). Saxifraga oppositifolia holds its position up to late stages of succession and is common in old growth tundra. In contrast, B. purpurascens is frequent in initial stages of succession, but its abundance decreases in later stages, becoming limited to disturbed places in old growth tundra (Moreau et al. 2008; Prach et al. 2012).

Saxifraga oppositifolia is a long-lived perennial clonal species, which regenerates both from seeds and vegetative diaspores. In the study area, young plants are prostrate, non-clonal and have a main root. Older plants produce adventitious roots on branches and start to disintegrate from old parts (Klimešová et al. 2012). Branches can be deposited by runoff water and re-root (Hagen 2002). Saxifraga oppositifolia produces a large number of tiny, well-dispersed seeds forming a long-term persistent seed bank (Cooper et al. 2004; Schweinbacher et al. 2010; Müller et al. 2012). The species is facultatively mycorrhizal, forming arbuscular mycorrhiza or can be non-mycorrhizal (Harley & Harley 1987).

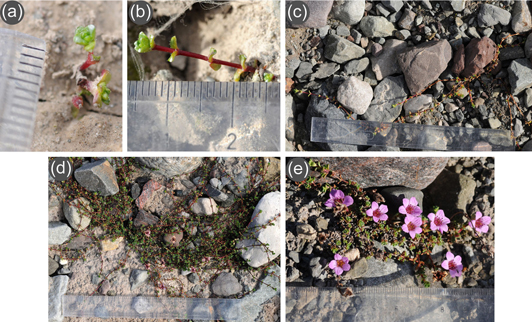

Saxifraga oppositifolia displays great morphological, genetic and ploidy variability through its circumpolar Arctic and alpine distribution, including Svalbard (Müller et al. 2012). There are two main morphological forms: prostrate and cushion (Kume et al. 1999; Kume 2003). Most plants in this study were growing on young substrate (less than 15–20 years) and were too young and small (Fig. 2)—often just a single unbranched shoot—to be classified into a growth form. Nevertheless, the vast majority of older plants (ca. 95%) clearly belonged to the prostrate form, with only five clear cushion-type plants found at sites 2–5 of the Sven foreland.

Fig. 2

Variation in shoot size and architecture of Saxifraga oppositifolia plants growing on the gradient on the Hørbye glacier foreland: (a) seedling with less than 1 cm2 cover in the initial succession stage (9 years since deglaciation); (b) a small sterile plant in the initial succession stage (9 years since deglaciation); (c) a more advanced sterile plant with longer shoots (11 years since deglaciation); (d) a loose tuft forming plant with few flowers (13 years since deglaciation); (e) a dense tuft forming flowering plant (18 years since deglaciation).

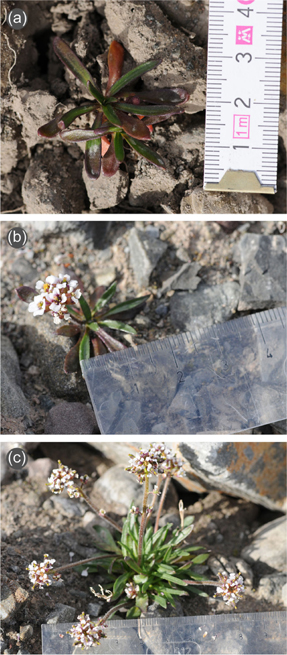

Braya purpurascens (syn. Braya glabella subsp. purpurascens) is restricted to the Arctic. It is a non-clonal plant with a perennial main root and one to several leaf rosettes and flowering stems (Klimešová et al. 2012; Fig. 3). Bledsoe et al. (1990) found no fungal colonization on roots for this species.

Fig. 3

Variation in shoot size and architecture of Braya purpurascens plants growing on the Hørbye glacier foreland: (a) a sterile plant with two rosettes (9 years since deglaciation); (b) flowering single-rosette (FS) plant (11 years since deglaciation); (c) flowering plant with multiple rosettes and inflorescences (11 years since deglaciation).

Data collection

Data on both study species were collected on forelands of four glaciers—Ferdinand, Hørbye, Ragnar and Sven, in Petuniabukta, northern Billefjorden, central Spitsbergen, Svalbard—in late July through early August 2011. A transect was established on each glacier foreland beginning at the closest occurrence of either of the studied species to the glacier front. The transects were ca. 1500 m long in the cases of the Ferdinand, Hørbye, Ragnar forelands, while the transect on the Sven foreland ended on the oldest LIA moraine. Using a global positioning system device, series of plots were placed along each time-since-deglaciation gradient at distances of 100, 300, 700 and 1500 m from the starting point (Fig. 1b). Plants were sampled from central parts of those plots until about 20 plants were sampled. Therefore, the sampled area was affected by the number of plant individuals on a site and plot size varied from about 100 m2 to several thousand m2. For each foreland, the age since deglaciation was derived from dates of glacier retreat presented by Rachlewicz et al. (2007; Fig. 2).

Up to 20 plants of each species were sampled at each site to determine the demographic structure of the populations. Saxifraga oppositifolia was the most frequent species and 20 individuals were sampled at most sites. In contrast, Braya purpurascens was in low abundance and rather scattered at most sites. Therefore, the B. purpurascens data set does not cover the whole glacier forelands in most cases and less than 20 individuals were sampled at many sites.

The following traits of S. oppositifolia individuals were measured: size of plant (product of length of the longest axis of a tuft and that orthogonal to it) and reproductive status of the plant (flowering/fruiting vs. sterile). For B. purpurascens, the reproductive status of the plant (flowering/fruiting vs. sterile) and number of sterile and fertile rosettes per individual were counted. The tuft size, number of rosettes or proportion of flowering individuals represent the demography of the population integrating age of plant individuals and variation in growth rates at different sites (Gatsuk et al. 1980).

Roots of five randomly chosen individuals of both species were collected at Ragnar and Hørbye forelands at the youngest inhabited site, at 300 m and 1500 m distant sampling sites. While S. oppositifolia individuals occurred at all the sampling sites, B. purpurascens was missing from the initial point and the 300 m distant site at Ragnar. Roots were washed, silica gel-dried for transport, and subsequently re-hydrated and stained by Chlorazol Black E following the procedure in Šmilauerová et al. (2012). Ten randomly chosen roots per species and sampling site were inspected by light microscopy.

Statistical analyses

Patterns of demographic population structure (i.e., size and reproductive status of plant individuals) of both study species along the gradients of the age since deglaciation were assessed by a series of generalized linear and non-linear models. Due to different shapes of the gradients on the four forelands, each foreland was analysed separately, though the data and graphical representation of the models were subsequently embedded in single figures. Saxifraga oppositifolia size was analysed by non-linear hyperbolic models with the following equation:

where a, b and c are parameters defining the shape of the relationship and age is the site age since deglaciation as derived from Rachlewicz et al. (2007). The size was log10-transformed prior to the analysis. This model assumes a greater size difference between plots in the young part of the age gradient than in the old part and an asymptote to which size will converge with the age. The asymptote is represented by the parameter c of the model. In addition, the projected intercept of the hyperbola with the x-axis (i.e., estimated age of the colonization start; back-transformed size 100=1 mm2) is fitted by the model and corresponds to age0=−a/c−b. Reproductive status of both S. oppositifolia and B. purpurascens was analysed by binomial generalized linear models. The demographic population structure of B. purpurascens, based on numbers of plants differing in reproductive status (flowering vs. sterile) and number of rosettes (single vs. multiple), was visualized by bar-plots and analysed by goodness-of-fit test as contingency tables where possible. All statistical analyses were conducted in R version 2.13.2 (R Development Core Team 2011).

Results

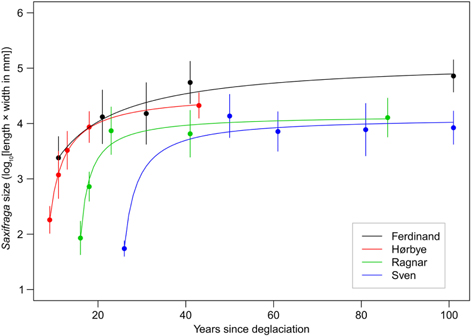

While both species occurred on the glacier forelands there was variability in their abundance, shoot architecture and size (Figs. 2, 3). Observed at all 20 sites, Saxifraga oppositifolia was confirmed as an omnipresent pioneer on the glacier forelands in Petuniabukta. We detected a clear relationship between the average size of S. oppositifolia plants and the time since site deglaciation (Figs. 4, 5, Table 1). Characterized by an initial steep increase of size but reaching a plateau on sites ca. 20 years older that the youngest occurrence (Fig. 5), this pattern was similar among the forelands but there were notable differences in the projected intercepts of model hyperbolas with the age axis, that is, estimated start of the colonization.

Fig. 4

Histograms of Saxifraga oppositifolia size distribution at individual sites on the glacier forelands under study. Each glacier foreland is represented by a row of plots. Reconstructed ages—expressed as years since deglaciation (ysd)—are given for each site.

Fig. 5

Patterns of Saxifraga oppositifolia size on the gradients of the age since deglaciation. Filled points represent mean values within study sites; error bars represent one standard error. See Table 1 for summaries of non-linear models describing the relationship between S. oppositifolia size and the years elapsed since deglaciation.

Table 1 Summary of non-linear hyperbolic models describing the patterns in size of Saxifraga oppositifolia individuals on the gradients of the age since deglaciation on the individual glacier forelands. The hyperbola parameter c corresponds to the asymptote to which size converges with the age; age0 (=−a/c−b) is the projected intercept between the hyperbolas and the x axis, which corresponds to an estimate of the start of the colonization.

|

Hyperbola parameters |

|

|

|

|

| Glacier |

a

|

b

|

c

|

age0

|

r2

|

F

|

df |

p

|

| Ferdinand |

−27.68 |

4.57 |

5.16 |

0.8 |

0.23 |

9.54 |

3.97 |

<10−4

|

| Hørbye |

−7.77 |

−5.61 |

4.55 |

7.3 |

0.52 |

35.61 |

3.97 |

<10−6

|

| Ragnar |

−4.8 |

−13.86 |

4.15 |

15.0 |

0.50 |

32.74 |

3.97 |

<10−4

|

| Sven |

−7.06 |

−23.00a

|

4.11 |

24.7 |

0.56 |

41.28 |

3.97 |

<10−6

|

| aFor this parameter, a minimum limit of −23.00 was set manually to prevent an unrealistic behaviour of the model. |

The estimated start of colonization varied among the forelands (Table 1). At young sites (9–26 years since deglaciation), S. oppositifolia plants were just simple shoots a few centimetres long. These small seedlings (Fig. 2a; size less than two on the log-scale corresponding to cover ca. 1 cm2) were frequent at most sites younger than 20 years (Fig. 4). Only rarely did these plants also occur at older sites (Ragnar foreland: sites 2 and 3 with two and one individuals, respectively; Sven foreland: site 4 with one individual). Small sterile plants (Fig. 2b; size between two and three on the log-scale, corresponding to cover of ca. 1–10 cm2) were common. They were most frequent at young sites and were absent at the oldest sites of Ferdinand and Hørbye forelands. Plants of intermediate size (Fig. 2c; size between three and four on the log-scale, corresponding to cover of ca. 10–100 cm2) were common along the whole gradients with the exception of Hørbye, Ragnar and Sven youngest sites. Large plants (Fig. 2d, e; size larger than four on the log-scale corresponding to cover exceeding ca. 100 cm2) were common or prevailing at older sites but were still present in low numbers at most of the youngest sites. The proportion of flowering individuals in the populations increased with age since deglaciation (Table 2). Plants growing on the youngest sites were always sterile, with sparse flowering recorded at slightly older sites (ca. 20 years since deglaciation). Approximately 50% of the plants were flowering at sites older than 50 years.

Table 2 Summary of generalized linear models describing proportions of flowering individuals in Saxifraga oppositifolia and Braya purpurascens populations on the gradients of the age since deglaciation on individual glacier forelands. P-values are based on comparisons of the deviance values with a χ2 distribution with one degree of freedom.

|

Saxifraga oppositifolia

|

Braya purpurascens

|

| Glacier |

Explained deviance (%) |

Deviance |

Regression slope |

p

|

Explained deviance (%) |

Deviance |

Regression slope |

p

|

| Ferdinand |

9.1 |

12.20 |

0.023 |

<0.001 |

9.8 |

5.88 |

0.058 |

0.015a

|

| Hørbye |

10.7 |

10.74 |

0.060 |

<0.002 |

6.5 |

6.37 |

0.010 |

0.012 |

| Ragnar |

10.7 |

10.42 |

0.029 |

<0.002 |

Non-significant (p=0.13) |

|

|

|

| Sven |

13.9 |

19.27 |

0.038 |

<10−4

|

Non-significant (p=0.25) |

|

|

|

| aThe generalized linear model for B. purpurascens on the Ferdinand foreland is affected by an occurrence of just a single flowering plant at the oldest site of the foreland (Fig. 6). If this plant is omitted from the analysis, the result is still significant (explained deviance=7.2%, regression slope=0.057, p=0.040). |

Braya purpurascens occurred in scattered populations, and was missing from six of the 20 sampling sites and only one individual was found at three sites. As a result the B. purpurascens data set is less comprehensive than that for S. oppositifolia. Nonetheless, some inferences can be made. Both species were able to colonize young sites. Braya purpurascens did not show clear patterns of demographic structure across the foreland gradients (Fig. 6). The youngest cohort of sterile, single rosette plants (Fig. 3a) and the most advanced flowering, multiple rosette (Fig. 3c) cohort co-occurred at most sites (although the flowering multi-rosette plants were missing from the youngest sites of Ferdinand and Hørbye; Fig. 6). There was a positive relationship between the occurrence of flowering and the age since deglaciation on the Ferdinand and Hørbye gradients; see Fig. 6 for the increasing proportion of the flowering multi-rosette plants (see also Table 2).

Fig. 6

Bar-plots displaying population structure of Braya purpurascens at individual sites on the glacier forelands under study. Each glacier foreland is represented by a row of plots. Braya purpurascens plants were classified to following classes: sterile single rosette (SS), sterile multiple rosettes (SM), flowering single rosette (FS) and flowering multiple rosettes (FM). Reconstructed ages—expressed as years since deglaciation (ysd)—are given for each site. Contingency table-based tests of differences in population structure between sites within forelands: Ferdinand: χ2=17.4, df=4, p<0.002 (sites 1, 2 and 4 were only considered, FS category was omitted due to absence at site), Hørbye: χ2=17.7, df=9, p<0.05 (sites 2–4 were considered), Ragnar not tested due to representative population occurring only at site 5, Sven: χ2=3.7, df=6, p=0.71 (sites 2–4 were considered).

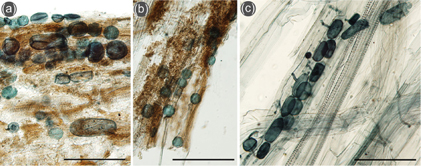

No arbuscular mycorrhizal structures were detected in the roots of both species. Both were free from infection at the Hørbye foreland. However, roots of both species contained resting and ripe sporangia typical of Olpidium (Fig. 7) on the Ragnar foreland. These structures were found at the three sampling sites (including the youngest succession stage) in S. oppositifolia roots and also in B. purpurascens roots at the oldest site (B. purpurascens was absent from the other two sampling sites).

Fig. 7

Fungal structures of Olpidium in roots of Saxifraga oppositifolia sampled at (a) Ragnar 1 (closest to the glacier foreland) and (b) Ragnar 3 sampling sites, and (c) Braya purpurascens at the Ragnar 5 site. The scale bars are 100 µm.

Discussion

The detected patterns in the demography of the widely distributed generalist Saxifraga oppositifolia support the expected pattern of increasing size and proportion of flowering individuals along the successional gradients. By contrast, no such trends were found in Braya purpurascens. Large flowering individuals of this species could be found at old and young sites (except for the youngest sites). Its scattered distribution on the forelands suggests this short-lived species is influenced by other environmental factors besides age since deglaciation. Together with its absence from mature tundra (our field observations and Moreau et al. 2009), these findings suggest B. purpurascens as a distinct specialized pioneer that deviates from the unidirectional, non-replacement succession pattern in the Arctic (Svoboda & Henry 1987; Prach & Rachlewicz 2012).

To the best of our knowledge, there is only one study evaluating size structure of plant population along a successional gradient in an Arctic glacier foreland. Mori et al. (2008) analysed demographic population structure of Salix arctica on a successional gradient spanning 35 000 years on Ellesmere Island, in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Despite the long time span of succession, the vegetation was very sparse, and small individuals of Salix arctica prevailed along the whole gradient despite increasing density and mean size of the individuals. Another study with which we can compare our results comes from an alpine area in southern Norway (Whittaker 1993). The author analysed size structure of six pioneer species and four late-successional shrubs. All but one showed ageing populations, where size correlated with age since deglaciation. Smallest plants prevailed in young successional stages with abundance decreasing, or plants were completely absent with increasing competition in later successional stages. The only exception was Oxyria digyna, a snow-bed specialist showing a variable size structure due to its special habitat demands (Whittaker 1993).

Our sites in Svalbard have higher precipitation than Ellesmere Island, but are drier and have shorter growing seasons than southern Norway (Serreze & Barry 2005). Therefore, it would be anticipated that successional processes in Svalbard would be shorter than Ellesmere and longer than southern Norway. Indeed, succession to a closed tundra community is estimated to take about 2000 years in Svalbard (Hodkinson et al. 2003). Although the glacier forelands in our study were characterized by sparse vegetation, the species studied were establishing successfully on new substrate whereas on older substrate, we did not find new seedlings (S. oppositifolia) or they were restricted to disturbed sites (B. purpurascens). Hence, the new substrate seems more beneficial for the establishment of these species than the old substrate, although the seed bank and seed rain increase with age (Cooper et al. 2004).

Young substrate in Arctic glacier forelands is characterized by high pH and lack of soil crust (Anderson et al. 2000); the studied species are therefore either supported in establishment by basic soil reaction or hindered by soil crust. Cyanobacterial crust is formed within 16 years of succession, when small individual S. oppositifolia and

B. purpurascens have become established (as observed by: Hodkinson et al. 2003, Moreau et al. 2005; Moreau et al. 2008; Prach & Rachlewicz 2012). We could therefore speculate that the two studied species need a fresh substrate without soil crust for seed establishment whereas later colonizing species may be unaffected or positively affected by soil crust. Diverse effects of soil crusts on seedling establishment are documented in the literature from warm desert conditions (Godinez-Alvarez et al. 2012) but only a positive effect is reported or expected from cold desert sites (Bliss & Gold 1999; Cooper 2011). Soil crust changes environmental conditions by increasing concentration of carbon, nitrogen, moisture and temperature, decreasing pH, and preventing soil churning in comparison with crust-free soil (Gold 1998; Hodkinson et al. 2003). Other studies, however, report cooling of the soil surface due to the soil crust and no effect of increasing nutrient availability on vascular plants (Gold et al. 2001). It is apparent that further research on soil crust ecology and vegetation development, along the lines of Yoshitake et al. (2010) and Moreau et al. (2005), in the pioneer stages of succession in Arctic glacier forelands is required.

Symbiotic associations with mycorrhizal fungi and dark septate endophytes are important for plants growing in nutrient-poor ecosystems (e.g., Newsham et al. 2009). However, they are perhaps not essential given the absence of these fungal mutualists in the roots of these pioneer species growing on recently deglaciated soils. Instead, structures of zoosporic fungal genus Olpidium comprising biotrophic pathogens were found. The genus Olpidium, formerly placed among Chytridiomycota, now has an uncertain phylogenetic position and is likely related to former Zygomycota (Sekimoto et al. 2011). Our finding add to evidence of the frequent occurrence of zoosporic fungi (including former Chytridiomycota) in high elevation or recently deglaciated Arctic soils (e.g., Jumpponen 2003; Schmidt et al. 2012).

Our study shows that B. purpurascens specializes on new or disturbed substrate lacking soil crust. While S. oppositifolia also establishes itself on new substrate, because of its longevity it persists in old growth tundra. These results imply that different plant strategies in primary succession can be recognized in the High Arctic, although they are probably only represented by a few species.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to M. Šmilauerová, P. Šmilauer, M. Kavková, K. Picard and A. Jumpponen for help with root staining and endophyte determination, Grzegorz Rachlewicz for determining the age since deglaciation of our sampling sites, and two anonymous referees for their helpful comments. The study was supported by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic through funding for CzechPolar—Czech polar stations: construction and logistic expenses (LM2010009).

References

Anderson

S.P.,

Drever

J.I.,

Frost

C.D.

&

Holden

P. 2000.

Chemical weathering in the foreland of a retreating glacier. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 64, 1173–1189.

Publisher Full Text

Bledsoe

C.,

Klein

P.

&

Bliss

L.C. 1990.

A survey of mycorrhizal plants on Truelove Lowland, Devon Island, N.W.T., Canada. Canadian Journal of Botany 68, 1848–1856.

Bliss

L.C.

&

Gold

W.G. 1999.

Vascular plant reproduction, establishment, and growth and the effects of cryptogamic crusts within a polar desert ecosystem, Devon Island, NWT, Canada. Canadian Journal of Botany 77, 623–636.

Publisher Full Text

Caccianiga

M.,

Luzzaro

A.,

Pierce

S.,

Ceriani

R.M.

&

Cerabolini

B. 2006.

The functional basis of a primary succession resolved by CSR classification. Oikos 112, 10–20.

Publisher Full Text

Cazarés

E.,

Trappe

J.M.

&

Jumpponen

A. 2005.

Mycorrhiza–plant colonization patterns on a subalpine glacier forefront as a model system of primary succession. Mycorrhiza 15, 405–416.

Publisher Full Text

Chambers

J.C. 1995.

Disturbance, life history strategies, and seed fates in alpine herbfield communities. American Journal of Botany 82, 421–433.

Publisher Full Text

Cooper

E.J. 2011.

Polar desert vegetation and plant recruitment in Murchisonfjord, Nordaustlandet, Svalbard. Geografiska Annaler Series A, 243–252.

Publisher Full Text

Cooper

E.J.,

Alsos

I.G.,

Hagen

D.,

Smith

F.M.,

Coulson

S.J.

&

Hodkinson

I.D. 2004.

Plant recruitment in the High Arctic: seed bank and seedling emergence on Svalbard. Journal of Vegetation Science 15, 115–124.

Publisher Full Text

Fujimura

K.E.

&

Egger

K.N. 2012.

Host plant and environment influence community assembly of High Arctic root-associated fungal communities. Fungal Ecology 5, 409–418.

Publisher Full Text

Fujiyoshi

M.,

Yoshitake

S.,

Watanabe

K.,

Murota

K.,

Tsuchiya

Y.,

Uchida

M.

&

Nakatsubo

T. 2011.

Successional changes in ectomycorrhizal fungi associated with the polar willow Salix polaris in a deglaciated area in the High Arctic, Svalbard. Polar Biology 34, 667–673.

Publisher Full Text

Gatsuk

L.E.,

Smirnova

O.V.,

Vorontzova

L.I.,

Zaugolnova

L.B.

&

Zhukova

L.A. 1980.

Age states of plants of various growth forms—a review. Journal of Ecology 68, 675–696.

Publisher Full Text

Godinez-Alvarez

H.,

Morin

C.

&

Rivera-Aguilar

V. 2012.

Germination, survival and growth of three vascular plants on biological soil crusts from a Mexican tropical desert. Plant Biology 14, 157–162.

PubMed Abstract

Gold

W.G. 1998.

The influence of cryptogamic crusts on the thermal environment and temperature relations of plants in a High Arctic polar desert, Devon Island, NWT, Canada. Arctic and Alpine Research 30, 108–120.

Publisher Full Text

Gold

W.G.,

Glew

K.A.

&

Dickson

L.G. 2001.

Functional influences of cryptobiotic surface crusts in an alpine tundra basin of the Olympic Mountains, Washington, USA. Northwest Science 75, 315–326.

Hagen

D. 2002.

Propagation of native Arctic and alpine species with a restoration potential. Polar Research 21, 37–47.

Publisher Full Text

Harley

J.L.

&

Harley

E.L. 1987.

A check-list of mycorrhiza in the British flora. New Phytologist 105, 1–102.

Publisher Full Text

Hodkinson

I.D.,

Coulson

S.J.

&

Webb

N.R. 2003.

Community assembly along proglacial chronosequences in the High Arctic: vegetation and soil development in north-west Svalbard. Journal of Ecology 91, 651–663.

Publisher Full Text

Jumpponen

A. 2003.

Soil fungal community assembly in a primary successional glacier forefront ecosystem as inferred from analyses of rDNA sequences. New Phytologist 158, 569–578.

Publisher Full Text

Kabala

C.

&

Zapart

J. 2012.

Initial soil development and carbon accumulation on moraines of the rapidly retreating Werenskiold Glacier, SW Spitsbergen, Svalbard Archipelago. Geoderma 175, 9–20.

Publisher Full Text

Klimešová

J.,

Doležal

J.,

Prach

K.

&

Košnar

J. 2012.

Clonal growth forms in Arctic plants and their habitat preferences: a case study from Petuniabukta, Spitsbergen. Polish Polar Research 33, 421–442.

Kohn

L.M.

&

Stasovski

E. 1990.

The mycorrhizal status of plants at Alexandra Fiord, Ellesmere Island, Canada, a High Arctic site. Mycologia 82, 23–35.

Publisher Full Text

Kume

A.,

Bekku

Y.S.,

Hanba

Y.T.

&

Kanda

H. 2003.

Carbon isotope discrimination in diverging growth forms of Saxifraga oppositifolia in different successional stages in a High Arctic glacier foreland. Arctic, Antarctic, and Alpine Research 35, 377–383.

Kume

A.,

Nakatsubo

T.,

Bekku

Y.

&

Masuzawa

T. 1999.

Ecological significance of different growth forms of purple saxifrage, Saxifraga oppositifolia L., in the High Arctic, Ny-Ålesund, Svalbard. Arctic, Antarctic, and Alpine Research 31, 27–33.

Publisher Full Text

Marcante

S.,

Winkler

E.

&

Erschbamer

B. 2009.

Population dynamics along a primary succession gradient: do alpine species fit into demographic succession theory? Annals of Botany 103, 1129–1143.

PubMed Abstract | PubMed Central Full Text | Publisher Full Text

Moreau

M.,

Laffly

D.

&

Brossard

T. 2009.

Recent spatial development of Svalbard strandflat vegetation over a period of 31 years. Polar Research 28, 364–375.

Publisher Full Text

Moreau

M.,

Laffly

D.,

Joly

D.

&

Brossard

T. 2005.

Analysis of plant colonization on an Arctic moraine since the end of the Little Ice Age using remotely sensed data and a Bayesian approach. Remote Sensing of Environment 99, 244–253.

Publisher Full Text

Moreau

M.,

Mercier

D.,

Laffly

D.

&

Roussel

E. 2008.

Impacts of recent paraglacial dynamics on plant colonization: a case study on Midtre Lovénbreen foreland, Spitsbergen (79°N). Geomorphology 95, 48–60.

Publisher Full Text

Mori

A.S.,

Osono

T.,

Uchida

M.

&

Kanda

H. 2008.

Changes in the structure and heterogeneity of vegetation and microsite environments with the chronosequence of primary succession on a glacier foreland in Ellesmere Island, High Arctic Canada. Ecological Research 23, 363–370.

Publisher Full Text

Müller

E.,

Bronken-Eidesen

P.,

Ehrich

D.

&

Alsos

I.G. 2012.

Frequency of local, regional and long-distance dispersal of diploid and tetraploid Saxifraga oppositifolia (Saxifragaceae) to Arctic glacier forelands. American Journal of Botany 99, 459–471.

Publisher Full Text

Nakatsubo

T.,

Fujiyoshi

M.,

Yoshitake

S.,

Koizumi

H.

&

Uchida

M. 2010.

Colonization of the polar willow Salix polaris on the early stage of succession after glacier retreat in the High Arctic, Ny-Ålesund, Svalbard. Polar Research 29, 385–390.

Publisher Full Text

Newsham

K.K.,

Upson

R.

&

Read

D.J. 2009.

Mycorrhizas and dark septate root endophytes in polar regions. Fungal Ecology 2, 10–20.

Publisher Full Text

Öpik

M.,

Zobel

M.,

Cantero

J.J.,

Davison

J.,

Facelli

J.M.,

Hiiesalu

I.,

Jairus

T.,

Kalwij

J.M.,

Koorem

K.,

Leal

M.E.,

Liira

J.,

Metsis

M.,

Neshataeva

V.,

Paal

J.,

Phosri

C.,

Polme

S.,

Reier

U.,

Saks

U.,

Schimann

H.,

Thiery

O.,

Vasar

M.

&

Moora

M. 2013.

Global sampling of plant roots expands the described molecular diversity of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Mycorrhiza 23, 411–430.

Publisher Full Text

Prach

K.,

Klimešová

J.,

Košnar

J.,

Redchenko

O.

&

Hais

M. 2012.

Variability of contemporary vegetation around Petuniabukta, central Svalbard. Polish Polar Research 33, 383–394.

Prach

K.

&

Rachlewicz

G. 2012.

Succession of vascular plants in front of retreating glaciers in central Spitsbergen. Polish Polar Research 33, 319–328.

Rachlewicz

G.,

Szcucinski

W.

&

Ewertowski

M. 2007.

Post-“Little Ice Age” retreat rates of glaciers around Billefjorden in central Spitsbergen, Svalbard. Polar Biology 28, 159–186.

Raffl

C.,

Mallaun

M.,

Mayer

R.

&

Erschbamer

B. 2006.

Vegetation succession pattern and diversity changes in a glacier valley, central Alps, Austria. Arctic, Antarctic, and Alpine Research 38, 421–428.

R Development Core Team. 2011. R: a language and environment for statistical computing.

Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

Řehounková

K.

&

Prach

K. 2010.

Life-history traits and habitat preferences of colonizing plant species in long-term spontaneous succession in abandoned gravel sand pits. Basic and Applied Ecology 11, 45–53.

Publisher Full Text

Schmidt

S. K.,

Naff

C. S.

&

Lynch

R. C. 2012.

Fungal communities at the edge: ecological lessons from high alpine fungi. Fungal Ecology 5, 443–452.

Publisher Full Text

Schweinbacher

E.,

Navarro-Cano

J.A.,

Neuner

G.

&

Erschbamer

B. 2012.

Correspondence of seed traits with niche position in glacier foreland succession. Plant Ecology 213, 371–382.

Publisher Full Text

Sekimoto

S.,

Rochon

D.,

Long

J.E.,

Dee

J.M.

&

Berbee

M.L. 2011.

A multigene phylogeny of Olpidium and its implications for early fungal evolution. BMC Evolutionary Biology 11, 331.

PubMed Abstract | PubMed Central Full Text | Publisher Full Text

Serreze

M.C.

&

Barry

R.G. 2005. The Arctic climate system. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Šmilauerová

M.,

Lokvencová

M.

&

Šmilauer

P. 2012.

Fertilization and forb: graminoid ratio affect arbuscular mycorrhiza in seedlings but not adult plants of Plantago lanceolata. Plant and Soil 351, 309–324.

Publisher Full Text

Svoboda

J.

&

Henry

G.H.R. 1987.

Succession in marginal Arctic environments. Arctic and Alpine Research 19, 373–384.

Publisher Full Text

Schweinbacher

E.,

Marcante

S.

&

Erschbamer

B. 2010.

Alpine species seed longevity in the soil in relation to seed size and shape: a 5-year burial experiment in the central Alps. Flora 205, 19–25.

Publisher Full Text

Väre

H.,

Vestberg

M.

&

Eurola

S. 1992.

Mycorrhiza and root-associated fungi in Spitsbergen. Mycorrhiza 1, 93–104.

Publisher Full Text

Whittaker

R.J. 1993.

Plant population patterns in a glacier foreland succession: pioneer herbs and later-colonizing shrubs. Ecography 16, 117–136.

Publisher Full Text

Yoshitake

S.,

Uchida

M.,

Koizumi

H.,

Kanda

H.

&

Nakatsubo

T. 2010.

Production of biological soil crusts in the early stage of primary succession on a High Arctic glacier foreland. New Phytologist 186, 451–460.

PubMed Abstract | Publisher Full Text